Copyright © 2016 by Ken Forkish

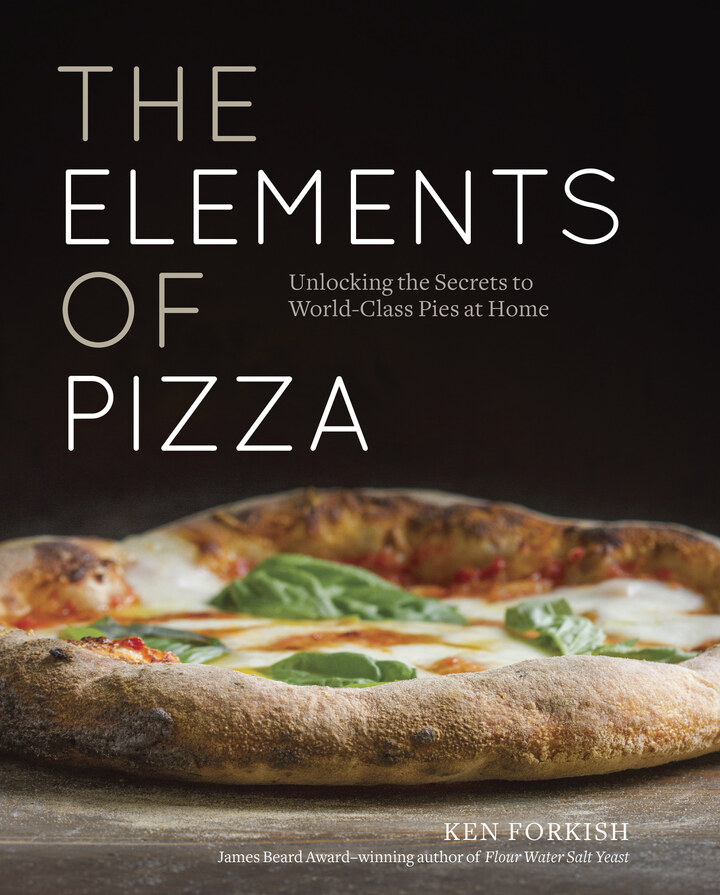

Photographs copyright © 2016 by Alan Weiner

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Forkish, Ken, author.

The elements of pizza : unlocking the secrets to world-class pies at home / Ken Forkish ; photography by Alan Weiner.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Pizza. I. Weiner, Alan (Alan S.), photographer. II. Title.

TX770.P58.F675 2016

641.82’48—dc23

2015032247

Hardcover ISBN 9781607748380

eBook ISBN 9781607748397

First Edition

v4.1

a

CONTENTS

The hidden reality of pizza is that you can easily make better pizza at home than you can buy at any but the best independently owned, quality-focused pizzerias. All you need are good ingredients—flour, canned tomatoes, and cheese—plus a few tools and a standard home kitchen oven. And some good instruction. Even if you live somewhere that has great pizzerias, imagine making your own—a pizza that you can be proud of and is exactly how you like it. Discover for yourself what different cheeses are like on pizza: splurge on water buffalo mozzarella, see what happens when you seek out caciocavallo cheese, or try adding freshly grated Pecorino Romano. Master thin-crust and Neapolitan-style pizza. Bang out a couple of killer pan pizzas to eat with Sunday football. Serve it with confidence to your family and friends. Making it yourself will give you a greater appreciation for the craft of the pizzaiolos at your favorite pizzeria: you will probably find yourself looking more closely at their shaping technique; the dough they use and its texture; and how it’s topped, loaded into the oven, and baked. By making pizza yourself, you become more intimate with it. It’s seductive. You are more informed, and that understanding leads to better pizza, great pleasure, and plenty of pride.

I grew up in Maryland, and I now live in Portland, Oregon, where I opened Ken’s Artisan Bakery in 2001 after a Silicon Valley career, first as an engineer and then as a sales guy. In 2005 we started making pizza once a week in our big bread oven at the bakery and called it Monday Night Pizza. Then, in 2006, I opened Ken’s Artisan Pizza, a wood-fired-oven pizzeria, with my head baker turned chef Alan Maniscalco. My third venture is a full-service restaurant called Trifecta Tavern & Bakery, open since 2013, where we include flatbreads on our dinner menu that are baked in yet another wood-fired oven. I’ve been to Italy about a dozen times. I wrote about pizza in my first book, Flour Water Salt Yeast. So, what did I know about pizza? Put it this way: the more you know, the more you know you don’t know. As it turns out, I had plenty left to learn.

Researching pizza for this book took me to Naples for the first time to visit its pizzerias. Many of the lessons I learned there opened my eyes to another way of thinking about pizza—especially about how to make the dough. It took a while to realize what was right in front of my eyes: think like a pizzaiolo, not like a bread baker. Pizza dough and bread dough have different needs. Bread wants to expand to its maximum volume; pizza does not. Pizza dough has structural needs—to stretch without breaking and without being too elastic. I knew this before, but I was still thinking of pizza as a kind of bread. The bread I like to make comes from wet doughs—made with a lot more water than you’re probably used to—but pizza doughs that are equally wet don’t work very well. And who knew that I should think about matching the hydration of the dough to the type of oven the pizza bakes in? At my pizzeria we long ago figured out the right dough for our oven. What I realized is that finding the perfect dough, and figuring out the perfect baking technique, is different when you’re baking in a standard home oven. What’s more, it depends on the style of pizza you want to make.

The best part of this little journey of mine was affirming that great pizza in the home kitchen is not complicated. It’s really very simple. On the pages that follow I take you through the process—how to make it—and the reasoning behind it so you can learn the same lessons I learned.

Even in Italy, more than 25 percent of households make their own pizza from time to time. It’s an easy meal that comforts—pizza baked in a pan in the home kitchen. I guarantee you can make better pizza at home than you would buy from any chain, and for less money, too. And it’s going to have heart. A decent home oven (not necessarily an expensive one); a baking stone, or better yet, a baking steel; a few baking accessories; good ingredients; and simple-to-follow instructions will get you there. (Trust me, you can buy affordable ingredients that are far better than any chain pizza place will put on your pie.) Making pizza can be a solo effort, where you enjoy the process as much as the result (and get better every time you do it), or it can be a tradition you share with your family or housemates.

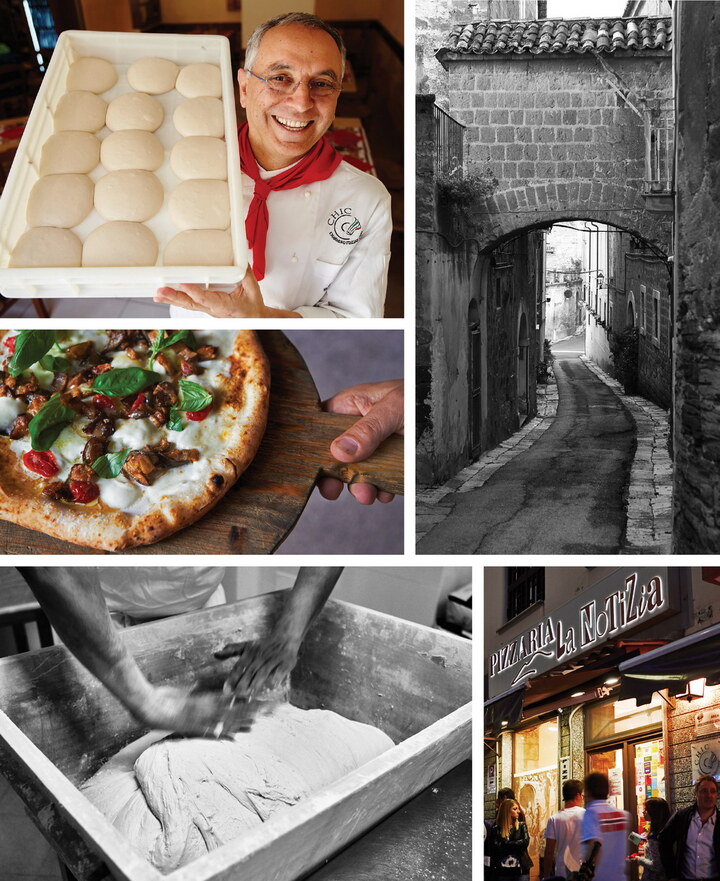

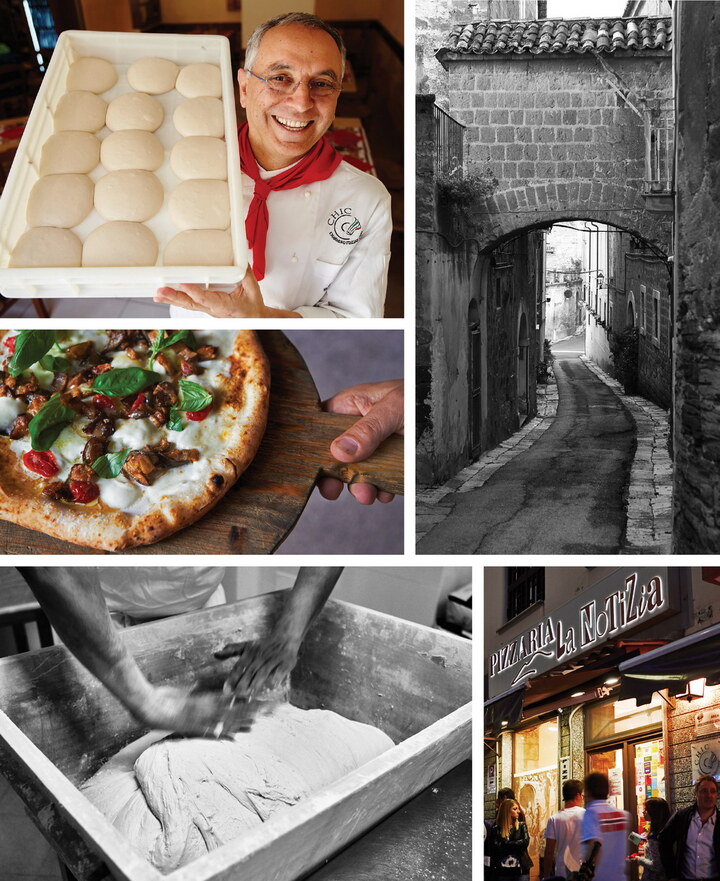

Great pizza as we know it has been happening in Italy for about 150 years, especially in the region surrounding the Bay of Naples. Great pizza is happening in America, too, with a dramatic growth in quality pies around the country in the twenty-first century. And this may not sound like news, but in the last several years a movement has grown that honors traditional techniques and ingredients, then goes beyond the standard to push the quality boundaries higher. It’s in the air. People are traveling long distances to eat pizza made by Franco Pepe at Pepe in Grani in the small village of Caiazzo, about a 45 minute drive from Naples. The queues at Pizzeria Bianco in Phoenix are legendary. Nancy Silverton’s ingredient-inspired Pizzeria Mozza in Los Angeles is known for brilliance on top of a great crust. The Salvo brothers in Naples select from seven different olive oils to match to their pizzas. Enzo Coccia at Pizzaria La Notizia in Naples is packing the house with a fantastic dough, perfectly baked and using the traditional ingredients of a TSG pizza, and then going beyond to source specific flours and toppings. “There are two pillars of pizza: the ingredients and the pizzaiolo,” according to one Neapolitan I met. Paulie Gee’s, Roberta’s, and Franny’s are killing it in Brooklyn and making their own distinctly New York versions of Neapolitan pizza, and Pierre Luigi Roscioli in Rome lists the provenance of his ingredients on his menu using things like Piennolo and Datterini tomatoes, culatello from Podere Cadassa, and mozzarella di bufala from Paestum.

I find great inspiration from all of these people. The pizzas from each of these places are all distinctly their own and reflect a variety of pizza styles. Should the pizza crust be spotted with char on its rim and underneath? Should it be stiff when you hold it on its end, or should it sag? What’s the best kind of cheese to use? Bread flour or Italian 00 flour? The answer to all of the questions is that it depends on what kind of pizza you are making, and even then there is plenty of wiggle room and individual variation. Let’s get this out right now: There is no one way to do it, no one right answer, no one platonic ideal of pizza that applies to everyone. Di Fara’s pizza on Avenue J in Brooklyn is nothing like the pizza at La Notizia, Salvo, or Da Michele in Naples, which are nothing like Frank Pepe’s in New Haven, Patsy’s in Harlem, Buddy’s in Detroit, Totonno’s on Coney Island, Delancey in Seattle, Anthony Mangieri’s Una Pizza Napoletana in San Francisco, or Pizzeria Bianco in Phoenix. All are terrific pizzas. That’s one thing that’s great about pizza, because depending on where you’re from and what kind of pizza is iconic in your memory, there is usually just one right answer to these questions. Pizza is a very personal experience. And you’re likely to forcefully defend your opinion, because in your mind this isn’t even a matter of debate—it’s a clear right and wrong and I’m stupid for suggesting otherwise.

This is a book that tells you how to make really great pizza at home in many styles—Neapolitan, Roman, American pan, New York, creative flatbread, gluten-free. In my first book I wrote how I high-fived my dog, Gomez, when I discovered how good pizza from my standard home kitchen oven could be. Great pizza at home can happen and it won’t break your brain or your daily routine. It all starts with a good dough, and I’ve got you covered there.

The soul of pizza starts with Neapolitan pizza—the soul of pizza is Napoli. It started there and it’s a defining cultural emblem. And after making pizza professionally for a short nine years, I was lucky enough to travel to Naples—to meet some of Italy’s top pizzaiolos, go to a mozzarella di bufala farm and dairy, tour a tomato plant, and visit the flour mill that provides flour for most of Naples’s pizzerias with the idea that I would gather inspiration and knowledge to inform the writing of this book. When I sat down with people whose families had been making pizza for the last hundred years, I kind of had my ass handed to me—gently, for the most part—and I asked myself: Who am I to even think I could represent what pizza is all about? But you know what? I discovered that there is a deep tradition that defines this culture, these people, and their food, and we are lucky to have had it become part of our lives, too. Naples doesn’t own pizza, but it lives and breathes it like no other place. It’s kind of like I’ve been making some nice music for the last ten years, and then I meet Beethoven or Mozart. And these are beautiful people who are willing to share their knowledge and experience that came from generations of hard, hard work and attention to detail. Pizza is a way of life in Naples. It flows through the bloodline. But people everywhere get emotional about the pizza they love, be they from Rome, Detroit, New Jersey, St. Louis, Old Forge, Portland, or the five boroughs of New York City. My goal in this book is to honor the pizza makers everywhere, but to do that, I had to start in Naples. Naples is the root of all pizza that follows.

My first book, Flour Water Salt Yeast, was about bringing methods used in the best artisan bakeries into the home kitchen to make professional-quality bread (with a few pizzas included for good measure). This book has a similar aim, but this time I focus solely on pizza and draw inspiration from several of the best pizza makers in Italy and the United States. I have my own pizzeria too, of course, but instead of an insular “here’s the pizza we make” approach to this book’s recipes, I want to offer you something that’s more representative of the range of pizza styles and traditions that inspire me. These are practitioners of the pizza craft for whom pizza is the principal expression of their lives, and in Naples it is a fundamental part of a regional identity. I’m a big fan of them all. I ask myself what I can learn from them, and how to make my version of whatever they do best. Replicating is not the point. What’s theirs is theirs, and it is of their time and place. But I can look at a Detroiter pizza and make a pan pizza my way that is inspired by it. So here in this book I give you my take on pizza styles I admire.

If you have already read and used my first book, Flour Water Salt Yeast (FWSY), you will find here the same methods for measuring ingredients using a scale, mixing dough by hand in a small dough tub, and making your own wild yeast leavening culture. I made some refinements too, with recipes for smaller batches of dough than those that were in my first book, and for using smaller amounts of flour to start and maintain a levain. This book’s pizza dough recipes are streamlined, and they take less time to make than the pizza doughs in FWSY—but they make better pizza. I decided to abandon my bread baker’s point of view and instead adopt pizza-dough-making methods I learned that are widely practiced in Italy.

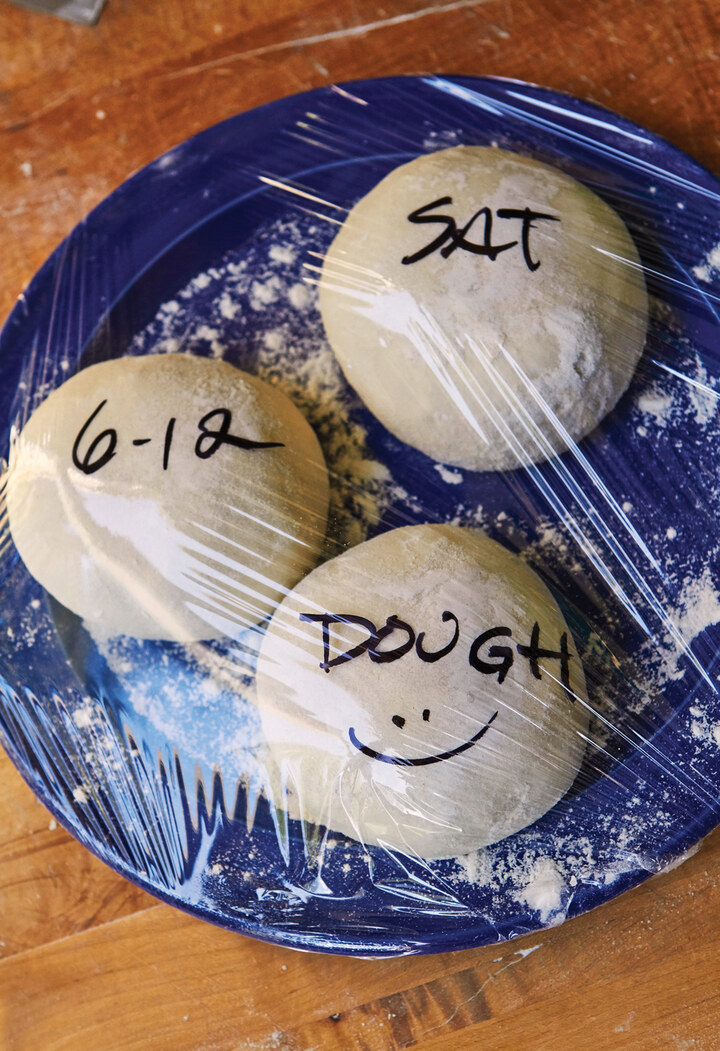

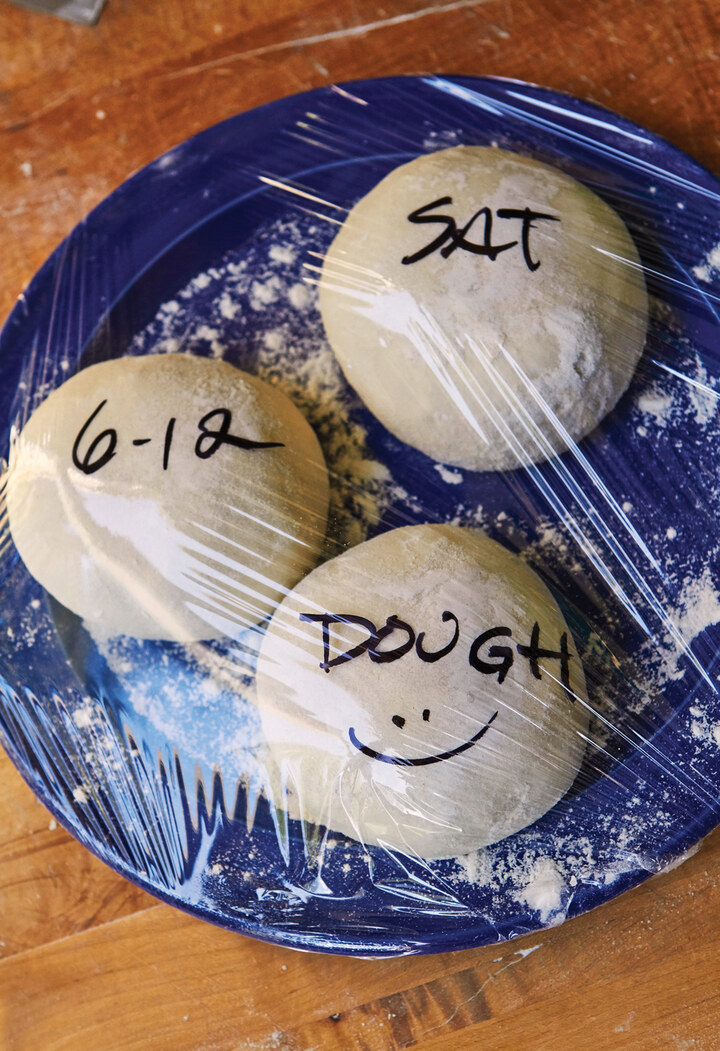

Also, as in my first book, I’ve tried to write with the understanding that you need some recipes for dough that work within what I’m assuming to be a standard workweek, where you probably go to work in the morning, come home in the evening, and don’t have a bunch of time to make dinner. My pizza doughs are long-fermented because that’s how you get the best flavors and textures—good flavors build while you sleep. This is ideal. So, as with my first book, time is treated like an ingredient, and I’ve highlighted the dough-rising schedule up front in each recipe. Mix a dough in the evening, shape it into dough balls (5 minutes) a couple of hours later, put them into the fridge, and when you get home the next night you fire up the oven and not much more than an hour after that you have an amazing pizza for dinner that was a total of 30 to 40 minutes of work. Or, maybe it’s a weekend, and you get up on Saturday morning deciding you want to have pizza that night but you were too wacked Friday night to even think about the next night’s dinner. Make a dough first thing in the morning, divide the dough into balls 2 hours later, fire up the oven in the evening, pop open a bottle of wine, put on La Traviata, and the world is yours. Do all your Saturday stuff in between. Be a hero.

“You always have pleasure in doing your thing well; it must give you independence from the whole buffoonery into which we have been born.”

—Albert Einstein

All you have to do is learn the method, and after a few repetitions you won’t even be looking at the instructions anymore; you’ll maybe just double-check the recipe for ingredient quantities.

If you’re feeling more ambitious, I have a dough recipe that uses a pre-fermented dough called biga. And if you really want to go the distance, I show you how to make a naturally leavened dough that uses your own starter and no commercial yeast. You can use any of these doughs—naturally leavened, made with pre-ferments, or straight—to make one of several styles of pizza: Neapolitan; Roman-style with a super-thin, crackery crust; American pan pizzas and bar pizzas; and New York–style classic hearth pies. You can integrate excellent pizza, made at home just the way you like it, into a busy lifestyle. If you want to splurge on ingredients, go for it. If you want to do it on a budget, you can do that, too—and still spend less and make a better pie than you would buy out. Maybe for you pizza making is about engaging your family or housemates in the effort. Maybe it’s a solo pursuit where you take pride in geeking out on the details. Pick your crust. Pick your toppings and sauce. It’s showtime!

CHAPTER 1

THE SOUL OF PIZZA

In 2014, a trip to Italy changed my thinking about pizza forever. I was moved by the way the people I met in Naples relate to pizza: for them, it was a soulful connection, related to the bigger picture of who they are as a culture. And then I became interested in the stories of the immigrants from Naples and the south of Italy who began making pizza in the United States in the early 1900s. I wanted to learn how pizza evolved from its early days to the present, how it stayed true to its roots in Italy, and how it grew to be its own thing in America. The stories always came back to the pizza maker, and how his or her passion was as important as the quality of the tomatoes.

ITALY

Enzo Coccia, a globally celebrated Neapolitan pizzaiolo, altered my pizza reality when he made me stare at a naked truth I had not confronted directly before. “Pizza is not the same as bread,” he said, and I’m glad he said it with force. Meaning I needed to adjust my thinking.

I set out to understand pizza’s place in the culture, which means understanding its history and the role it plays in people’s lives, and meeting the people making it today. During my visit, I focused on Naples and Rome. Naples, because it is where pizza began. Neapolitans bleed pizza—it is a defining element of who Neapolitans are and how they live. Rome, because it has two distinct styles of pizza that I admire: one a super-thin crusted wood-fired-oven style; the other called al taglio, served by the slice, which is found in bakeries. You will find pizza in both of these cities’ styles, with plenty of hybrids of the two, throughout Italy and beyond. In Bologna you will find very thin crust pizza like in Rome, but as a much larger pie, and in Florence it’s possible to find crust even thinner than in Bologna. In this book I focus on the styles of pizza that both interest me most and that I believe can be successfully adapted for the home kitchen. It inspires me that pizza making is not a static craft in Naples and Rome. The best pizzaiolos are pushing their skill to new heights, making extremely high-quality pizzas that are in harmony with tradition but not constrained by it. In my mind, this is the best evolution possible. It’s like jazz to me.

Naples

Naples is the birthplace of pizza, where by most accounts it took its modern form in the 1700s, without tomatoes—which, though they were first imported to southern Italy in the 1500s, probably didn’t make it onto pizzas until the 1800s. Establishing firm timelines for specific evolutionary steps in pizza history (or for any other food that began as a street food) is difficult. One of the earliest Neapolitan pizzerias in the written record is Zi Ciccio, first written about in 1727, located in the Piazza Cavour. Others from that era include Port’alba and, in Porta San Gennaro, the pizzeria Capasso. According to one account, the most successful was called Ntuono, run by Antonio Testa near the church of Santa Teresa, where King Ferdinand I (1751 to 1825), the ruler of Naples, secretly went to eat. Did he wear a wig? (It wasn’t the public he was hiding his pizza habit from; it was his wife, Queen Maria Carolina of Austria, Marie Antoinette’s sister, who apparently dominated her unsophisticated husband and ruled the Kingdom of Naples in his name.)

Earlier forms of pizza described in the sparse historical record were made with eggs, sugar, almonds, and spices and were not food for the commoner but rather for the ruling classes. But the early modern Neapolitan pizzas of the 1700s were indeed for people on the street who were hungry and either had a little money or bought their pizza on credit using a Neapolitan pay-it-forward system that is still in use today. Toppings included inexpensive local ingredients like olive oil, garlic, oregano, grated cheese, lard, and salt. When tomatoes started appearing on pizzas in the 1800s, they would have only been used during their fresh season from late spring through summer and autumn (or, possibly, as a conserva during the winter and spring). By the early 1900s they were being commercially canned in southern Italy and thus were available year-round. Pizza has been called il sole nel piatto—the sun on a plate—and Naples is famously sunny, hot in the summer and temperate in the winter (perfect for out-the-window laundry drying). The climate, the sea air, and the volcanic soil make an excellent terroir for tomatoes, olives, and herbs. Tomato on pizza was magic waiting to happen.

Modern pizza started as a street food for the working classes (and the occasional disguised king), but became an obsession across Neapolitan society once Queen Margherita famously ate what became her namesake pizza at Pizzeria Brandi in 1889. Pizza was sold in outdoor stalls and was also vended by boys carrying pails, called stufa, full of baked, folded pizzas. “In Naples we call these portafoglio, folded like a packet,” a taxi driver in Naples told me. Marinara pizza got its name because it was a favorite among fishermen (mariners), who would take it on board to eat during their workday, folded over upon itself to make it easily transportable. Nowadays we think of “marinara” as referring to an iconic red sauce, but in fact, in its early days the marinara pizza was just topped with garlic, oil, and oregano. Tomato sauce didn’t enter the equation until later. According to a book published by the Molino Caputo flour company (Teri, Oggi e…Domani, la Pizza tra passato e future), the first pizza to have a proper name was called the mastunicola, made by the wife of a mason, Mastro Nicola, to fortify him for a hard day’s work. According to sources, it was topped with cheese and lard. I take most of these recorded “facts” with a grain of salt—the research is scanty and one author’s assertion becomes another’s fact. Still, I like imagining Mastro Nicola going to work with his namesake pizza in his satchel, clueless to his future fame. But didn’t his wife have a name, too?! She made the pizza!

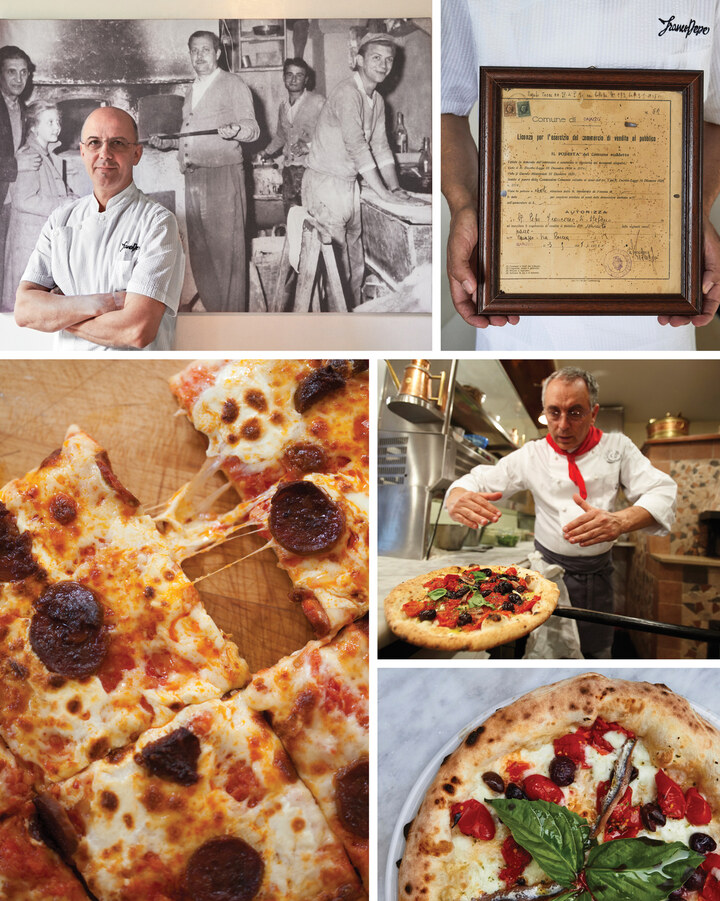

Today, Da Michele might be the most popular of the traditional, old-school pizzerias in Naples. It’s often just called “Michele” by locals, who queue up for one of the eight hundred pizzas (!) made daily at this iconic spot in the middle of the city. Da Michele, founded in 1870 and in its present location since 1930, makes two kinds of pizza: marinara and margherita, costing 4 euros each, 5 euros if you want double cheese on your margherita. There is an old framed poster on the wall at Da Michele; here is a rough translation:

With garlic, oil, and oregano

Or with tomato rather

It seems an easy thing

But making pizza is far from easy

You do not want a soft dough

You need to know how to bake

The flavor comes from he who prepares it

And it’s something wholesome and good

Pizza was born in Naples

But few in the trade

Can enable you to fully enjoy

The pleasure of eating it

Only Don Michele

A pastry chef of refined skill

Makes a pizza so splendid

It will comfort you and make you happy

The original pizzas were made from simple, local ingredients. The flour was from nearby wheat fields and mills; the small, pear-shaped tomatoes that ended up as pizza sauce stared at Mount Vesuvius from the valley floor as they ripened in the ever-present sunshine. Olive oil, oregano, garlic, and mozzarella cheese were all from Campania too. Neapolitans get emotional about the pizza they love. “Pizza isn’t just a food, it’s a way of being Neapolitan,” Enzo Coccia once said in an interview with video journalist Sky Dylan-Robbins.

Pizzeria Brandi, Starita, Di Matteo, Gino Sorbillo, and Pizzeria Port’Alba are but a handful of the classic, old-school Neapolitan pizzerias that serve the platonic form of Neapolitan pizza, a cheap food for all walks that is primal sustenance for the people of Naples. “They are selling an emotion,” said Costantino Cutolo from the tomato processor Compagnia Mercantile d’Oltremare, who grew up just outside of Naples. Other pizzerias, like La Notizia, Salvo, and Pepe in Grani, are still firmly based in tradition, yet focus extra attention on the quality of the dough. They also push the boundaries of what goes on top of the pizzas, thinking more freely but still intent on using the bounty of Campania’s land and sea.

The craft of the pizzaiolo has been handed down from generation to generation. They are not chefs, nor bakers—they are pizzaiolos. It is a very proud and respected profession. Naples is awash in pizzaiolos today who are third- or fourth-generation pizza makers. One said his grandfather, a pizzaiuolo (Neapolitan spelling), had twenty-one grandchildren and every one is a pizzaiuolo. It is a pride of Naples that they have the history and culture that produces generation after generation of serious, dedicated pizza makers for whom this craft is the one profession they will have all their lives. Their work is often a measure of respect for their fathers and grandfathers (there are some, but very few female pizzaiolos; I hope this changes). “The soul of pizza is the pizza maker,” Antimo Caputo, of the Molino Caputo flour mill in Naples, told me. Making pizza isn’t just a mechanical act. “It has to be made with love to be good,” Antimo continued. “He puts in the pizza his passion.”

I asked most of the people I met in Naples how often in a week they eat pizza. The answer usually began with a “pffffff,” as whomever I was talking with had to stop and think to answer this ridiculous question, which is apparently akin to, “How many times a week do you think about sex?” The answer ranged from once a week to too many times to count. Neapolitans are very social, and meeting up with friends at a pizzeria is a very common weekly thing.

Enzo Coccia is one of my pizza heroes, and I met him at his pizzeria, La Notizia. Enzo is a third-generation pizzaiuolo making some of the best pizza in Naples right now, and La Notizia won the Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana (AVPN) Best Pizza award for 2014, a great honor. Enzo is making pizza with a strong respect for tradition, but he also pushes accepted Naples boundaries by going beyond margherita and marinara, using ingredients you would more likely find in a great salumeria or a top restaurant. This is a touchy, controversial subject for Neapolitans!

In a 2012 article, Sergio Miccu, head of the Neapolitan Association of Pizza Makers, is quoted as saying, “There is no such thing as gourmet pizza; we are not OK with this. Pizza was born as a food for the poor and any complicated pizza loses its identity.” While I don’t completely agree with Sergio—by his logic, anything other than margherita or marinara would be heresy—I appreciate his sentiment. There’s something to be said for preserving traditional pizza, which at its heart was commoners’ food. Putting expensive toppings on the pizza takes it out of that realm. This further explains something Enzo had said to me: “There are a thousand pizzerias in Naples. It’s difficult to succeed with high quality.” Many, maybe even most, Neapolitans aren’t seeking creativity or “gourmet ingredients” on their pizza, and many are offended by pizza that aspires beyond its working-class origins—preservation of traditional pizza is important and is one of the goals of the Neapolitan Association of Pizza Makers. Enzo Coccia is one of Naples’s most famous—and most controversial—pizzaiolos because he is creative and uses better- quality toppings than many of the traditional and more famous places, and charges more for it. Miccu might sneer at his “gourmet” approach, but for me, Enzo deserves admiration. And judging by the line on the sidewalk the last time I was there, he’s got nothing to worry about.

Enzo seems to have a particular point of view about pizza that is grounded in tradition yet a little bit poetic. But it seems modern, too. Maybe he’s a practical, yet very talented dreamer, willing and confident enough to take his own road, follow his own whim. As a craftsperson, what’s wrong with doing what you are inspired to do? It means you can choose pizza at La Notizia that’s traditional, or uniquely Enzo’s own. Others may copy him someday, but he is copying no one; rather, he’s building on two-hundred-some years of local pizza tradition and adding his own next step. For that, he has my admiration. And his pizzas are so good!

Enzo does not speak English, so when we sat down to talk pizza he brought one of his young cooks to sit with us and translate. I arrived at La Notizia with no particular agenda other than to meet him and see what I could find out about how he makes his dough. I was quickly schooled and quietly thrilled that my simple questions and honest curiosity were taken so seriously. Hopefully I’ll be a better pizza man for it. The conversation began with a one-on-one, gentle but stern, 15-minute lecture on the history of pizza—or pizza dough, to be specific. Until about 1920, all pizza was made with a natural levain (also known as a wild yeast culture), levitazione naturale in Italian, and each day’s batch was leavened with a piece of the previous day’s dough. Then, when commercial monoculture yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) became available in Naples around 1920, many pizzerias switched to this because it was less work and demanded less expertise, and was therefore sometimes more reliable. Commercial yeast, for all but the extremely talented pizzaiolos, produces a lighter, more delicate pizza crust, too. But they were still in the habit of using pre-fermented doughs, a portion of old dough to leaven the next batch as they had done before (this is called pâte fermentée in French baking). In the 1950s, many but not all pizzaiolos began making direct doughs (I called direct dough “straight dough” in FWSY), making their jobs once again a little bit easier and producing reliable results. From this point to the present, only a small number use refrigeration to extend the fermentation and stabilize the dough.

Today, the exact fermentation method varies from one pizzeria to the next—many use either a direct dough or mix with old dough to leaven the next batch—but almost all of them use commercial yeast and long, slow fermentation. Most pizzerias tend not to use refrigeration (it takes up valuable space and is an extra expense); instead, they store the dough in the pizzeria at room temperature and mix multiple batches daily, if necessary, to meet demand. The busiest pizzerias sell four hundred to eight hundred pizzas every day. Each dough ball has a window of about 4 to 6 hours for optimum performance when held at room temperature; if left too long, the dough will be too gassy to make a good pizza. What these pizzerias need to do is meet the volume requirements of their business with good dough balls every time.

Enzo shared his dough-making process, which kind of turned my way of making pizza dough on its head (more on this later). He asked me what I am: a pizzaiolo? Enzo said being a baker and being a pizzaiolo are different, and don’t assume because I know bread and croissants that I know pizza. His point wasn’t just that pizza and bread are different, it was that being a pizzaiolo is different from being a baker. The life is different, the dough is different, the baking is different. The end product is different. The oven is different. And pizza is not the same as bread.

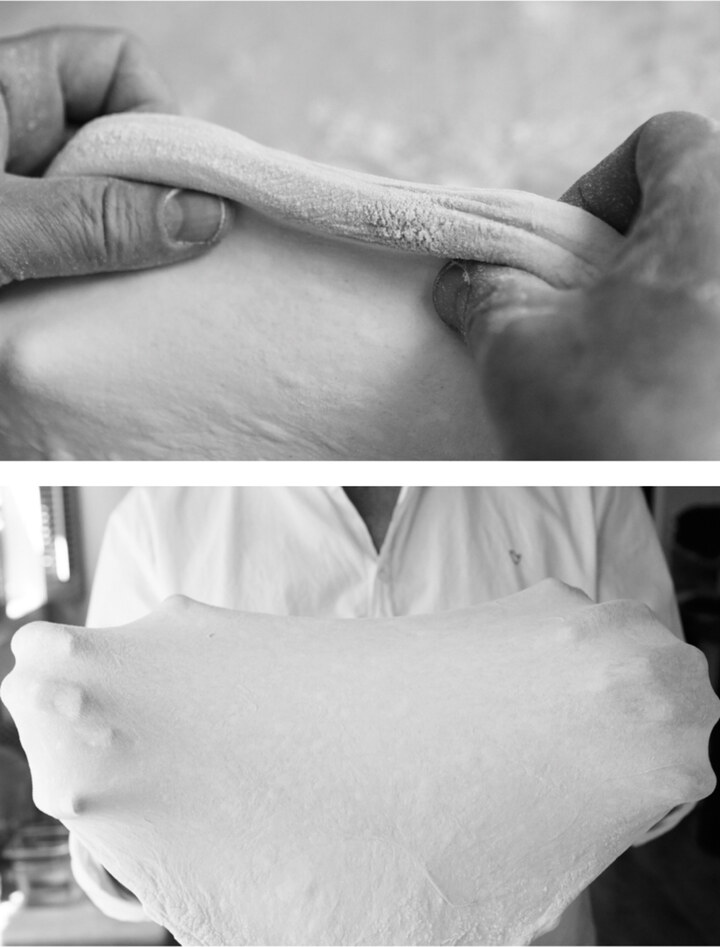

I felt humbled in Enzo’s presence, and a little intimidated. He didn’t crack a smile for ten, fifteen minutes. As he made his point that “making pizza is not the same as making bread,” he said it in a strong voice to communicate that this was inarguable, and to bring the point home, he showed me the palm of his hand. It was a strong hand, with the deeply creased palm of a longtime pizzaiolo who had shaped countless thousands of pizzas for decades. His pride was as strong as his hands. The classic Neapolitan pizzaiolo technique is to hand-cut dough balls out of a larger dough mass to make up hundreds of pizzas every day. It is a pincer motion, similar to how I hand-mix bread dough or cheese makers cut mozzarella (mozza means “to cut”). This repeated cutting motion works the palm creases over and over and over. Somehow, given enough time (decades) and enough dough balls (you do the math), dark gets in there. “Show me your palm” has some significance among pizzaiolos.

After a very serious conversation about pizza dough, Enzo’s warm Neapolitan heart took over and we ended up smiling, and with a mutual respect. When I pulled out my pen and started taking notes, he looked at my notes, and could tell I know my dough, and then he opened up and really told me his exact dough recipe and process. He said pizza dough has just four ingredients, plus time. I added “and temperature,” and showed him the part in Chapter Two of FWSY where it says to “think of time and temperature as ingredients.” Enzo nodded his head and beamed at me. I asked if he would give me permission to include his way of making pizza dough in my new cookbook, and he agreed so long as I would say it’s not the same as coming to his restaurant. (Duh, of course it’s not.)

While I am a strong advocate for using traditional methods in bread, pizza, wine, salumi, agriculture, and so on, I also latched on to what, to me, seems like a new generation of pizzaiolos in Italy and in the U.S. They are (or more hopefully, we are) making great pizza by carefully respecting tradition yet topping the pizzas with rational creativity. Using artichokes and fresh goat cheese, smoked provolone and escarole, figs and honey, or the best culatello I’ve had in my life—this is a good thing. Yes, these pizzas cost more than the 4-euro pizza at Da Michele, but boy are they good to eat.

Pizzeria Salvo is another example of a great modern-day pizzeria in Naples. The brothers at Salvo, Francesco and Salvatore, use seven different olive oils to top their pizzas, depending on which olive oil goes best with which pizza. Their brother Ciro Salvo’s place, Pizzeria 50 Kalò, is another example of a younger yet experienced pizzaiolo pushing pizza’s quality boundaries. Neapolitan trash talking (in the press and in personal interviews) suggests that many of the old-school, classic pizzerias were using ingredients of low quality. Still, when you think of pizza as a humble food for commoners, it kind of makes sense that they would use cheap ingredients, but inexpensive doesn’t always mean poor quality. I think this bad-quality-ingredients reputation is only a partial truth, knowing that most use good flour from Caputo, and how bad are the tomatoes and mozzarella from this region going to be? Maybe they use inexpensive oil. What is notable about the Salvo brothers and others that I’m writing about is that now a select group of pizzaiolos is making their reputation with the highest quality ingredients: specifically selected tomatoes, garlic, cheese, oregano, basil, and olive oil. A simple marinara pizza from these impeccable local ingredients becomes an exceptional thing, especially when married with an excellent dough and expertly baked. Take, for example, Ciro Salvo at 50 Kalò. He’s certified by the Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana (AVPN) but goes beyond that to specifically source garlic from Campania’s Ufita valley, oregano from the Alburni mountain villages near Salerno, and olive oil from Don Alfonso 1890 on the Amalfi coast.

What strikes me as funny is that a classic, old-school pizzeria in Naples—Starita—has sixty-eight different pizzas on its menu, with toppings as varied as mortadella on pistachio cream, yet La Notizia is controversial for making “gourmet pizza.” Familial slings and arrows is all this hubbub amounts to, but it’s a great indicator of how seriously they take their pizza.

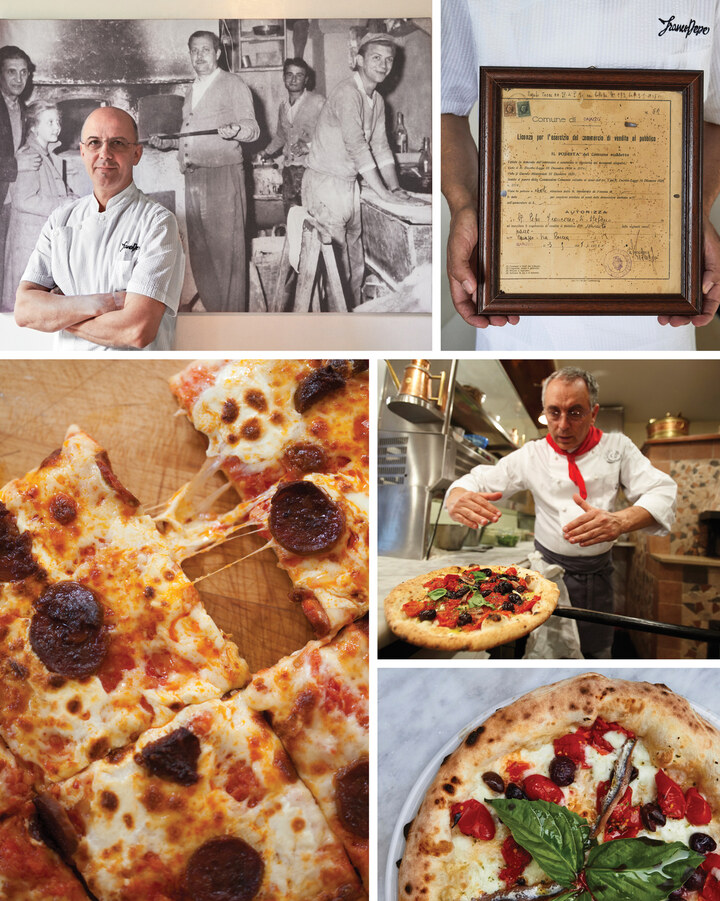

Caiazzo

About 50 kilometers (30 miles) outside of Naples, the small, old village of Caiazzo has a beautiful church built around the ancient tomb of Santo Stefano, narrow alleyways, all-stone buildings, a courtyard, and atmospheric lamplit cobblestone streets. The surrounding valleys of Caserta, one of the regions where mozzarella di bufala is made, are fertile with volcanic soil, painted with gentle hills and farmland. This region is a mecca for produce. Outside of the church, the other landmark of Caiazzo is Pepe in Grani, a new pizzeria in a very old stone building that fashions a modern-day pizza built on the foundation of pizza history. Opened in 2012, Pepe in Grani was constructed in a restored circa 700 AD stone building as a place for pizza, research, and hospitality. Franco Pepe is a third-generation pizzaiolo. In 2014, Jonathan Gold pronounced it the Best Pizza in the World in Travel & Leisure magazine. On this trip I brought April, one of the managers from my pizzeria, and we visited Franco and had an epic dinner, two of us eating a crazy six pizzas. “Are you sure?” Franco kept asking, repeatedly checking on us with an amused grin while we ate. I couldn’t travel all this way just to have one margherita, and the menu offered a “tasting menu” of five pizzas for three or four people. It would have been rude to sample each and send back the bones waiting for the next pie, so we just dove in. No regrets, either! Dough-wise, Franco follows the traditional methods of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: naturally leavened pizza dough, hand-mixed, no refrigeration. His ingredients are all from his area, seasonal (for example, figs, artichokes, sweet onions, cherry tomatoes, and fresh anchovies from the nearby coast), and of stunning quality. Best pizza in the world? Let’s just say, at Pepe in Grani the dough is mixed perfectly, fermented perfectly, shaped perfectly. The toppings are in perfectly complementary proportions. And, naturally, the pizza is baked perfectly. These were flawless pizzas. His reputation is well deserved. The crust had a very thin layer of crisp on the outside and the bottom, and a feathery light crumb inside the rim. It was almost weightless. The inner base of the crust was very thin and perfectly leopard-spotted on its bottom from the oven’s floor. On this, our fifth consecutive day of eating pizza, April said, “I’ve never had anything like that, ever.” I can’t print the rest of what she said, but it was definitely complimentary.

Our tasting menu at Pepe in Grani was preceded by a folded-over libretto pizza filled simply with tomato sauce, garlic, and fresh oregano, wrapped in brown paper. The libretto, aka portafoglio, remains Naples’s street food, and while later pizzas went in the gourmet direction, Franco started us with this basic pie—where pizza began. I love this respect for tradition. Franco’s crust tasted of lactic fermentation—a flavor that’s sometimes described as milky and fruity, and similar to what you get with a ripe liquid levain (or, for anyone who’s baked out of my first book, from my White Flour Warm Spot Levain Bread). His is a very well-fermented dough, with a beautiful balance of flavors, and as they might say in Italy, it is highly digestible (“digestibility” is loosely defined, but widely regarded as being a benefit of long-fermented, naturally leavened pizza and bread). We put that to the supreme test by eating five more pizzas: a traditional margherita pizza with mozzarella di bufala; a pizza with white fresh anchovies, olives, split Vesuvio tomatoes, and oregano; a folded-over pizza with escarole, ham, and smoked provola (the crust was so soft, so delicate, so delicious); artichoke with melted mozzarella and a light fresh ricotta piped on after the pie was baked; then the fig jam pizza with Conciato cheese grated over after baking. The pizzas looked bready and doughy, but they were ethereally light. Tender. Delicate. Sexy.

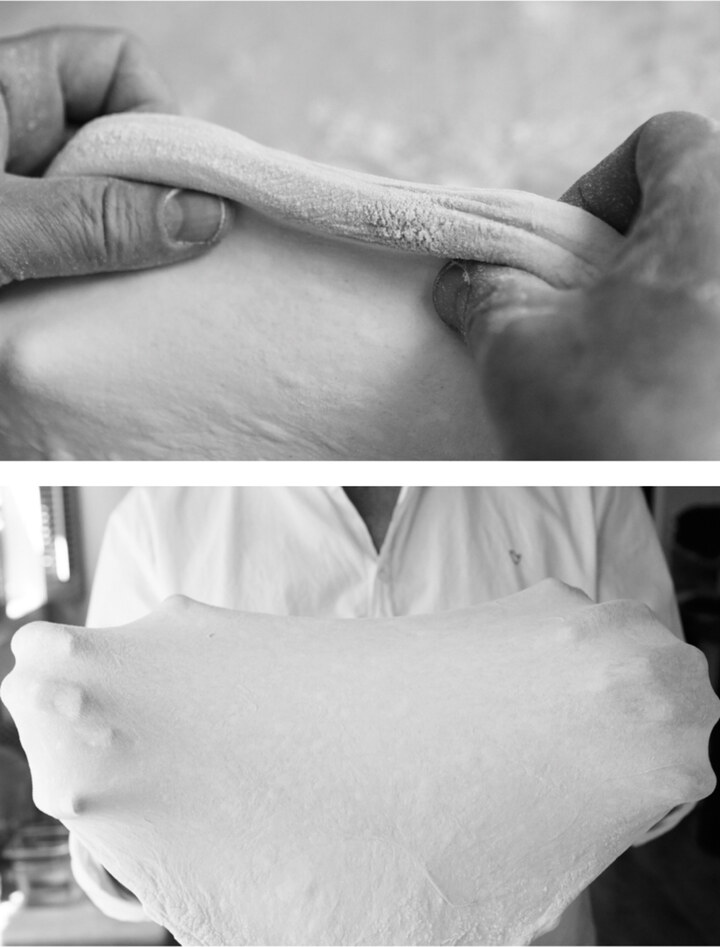

I mention that Franco Pepe makes his dough the old-fashioned way, by hand—but this is a point worth reiterating, because it’s ridiculously hard work. Imagine mixing 80 kilos (175 pounds) of dough by hand for 20 or 30 minutes. At the end of the day, so it has time to rise before the next day’s service. Franco said to us, “My pizza is slow food.” He is fond of saying his pizza is “wireless,” meaning no electricity is used anywhere to make it. He mixes it in wooden boxes, and it never sees refrigeration. He uses thin, symmetrical pieces of wood to fire his gold-tiled Stefano Ferrara oven, ensuring even performance.

Pepe in Grani wants to communicate and promote the area’s bounty through its pizzas. Franco has worked with local farms and a local agronomist, Vincenzo Coppola, in one case to revive an ancient indigenous variety of wheat, and in other cases to showcase the local tomatoes, garlic, onions, chickpeas, fruits, and so on. This work and his growing fame have helped revive a declining local economy.

Not content to simply make pizza the same way every day, Franco Pepe continues to experiment with different flours and adjustments to the fermentation of his dough. I get this, and I find inspiration from others like Franco, who are driven to experiment and look for the new in themselves and the world around them. It’s one thing to experiment; it’s entirely another thing to experiment and make it something we all swoon over. Franco Pepe’s gift is combining ingredients that serve as a window on the region that he is proud of, and making them into pizza that stands at the pinnacle of pizzadom. He recognizes that many of the old ways are still the best, even if they mean harder work and more time. My thinking is that by doing something over and over with an open mind, not just repeating but learning, and respecting tradition but building on it with your own inspiration—that’s when new realities, new beautiful things, can happen. Learning from each experiment and applying it the next time is what leads to greatness.

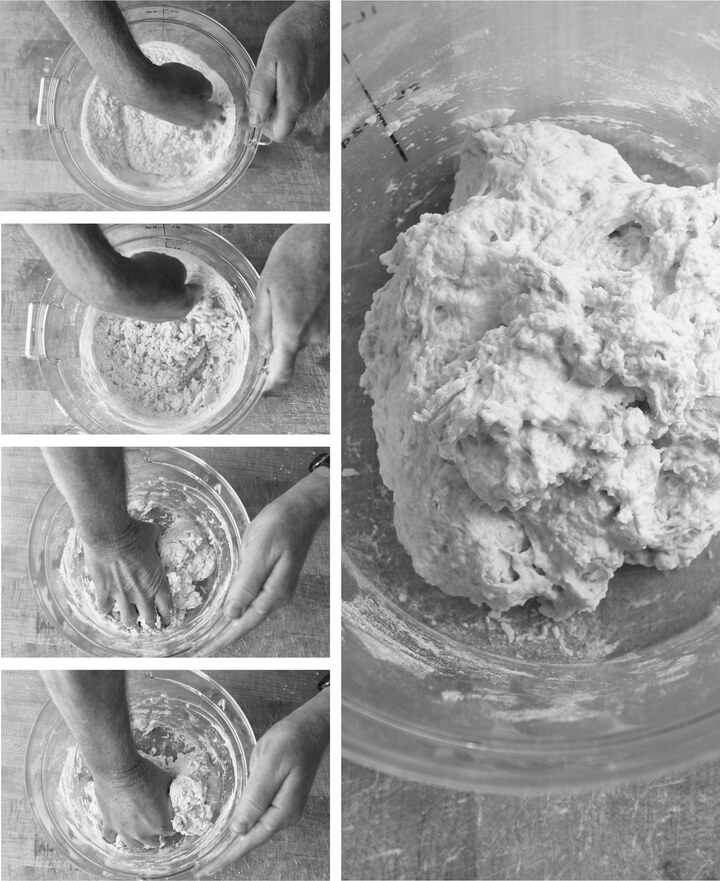

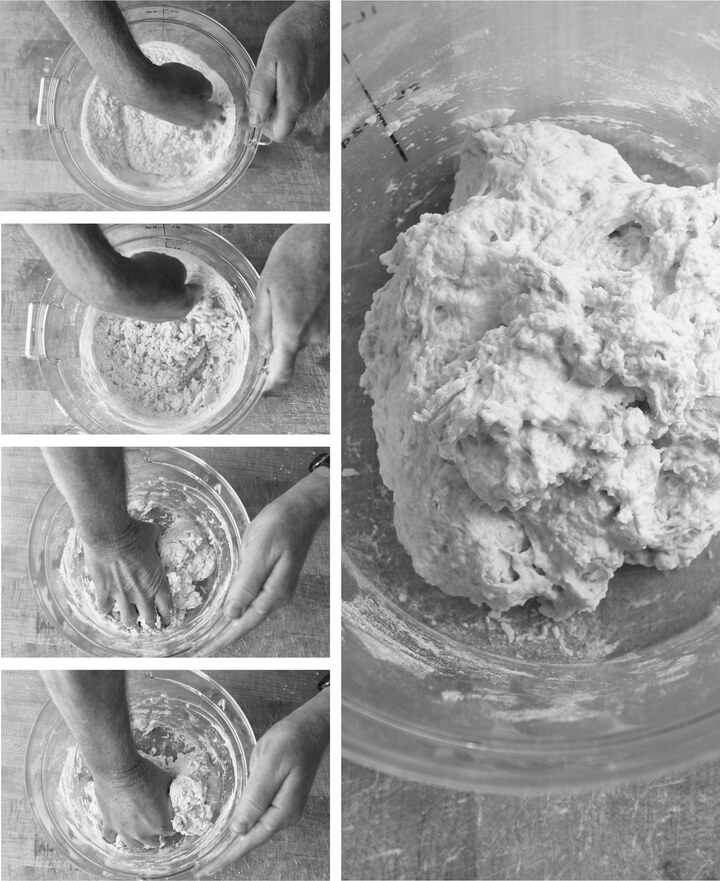

To return to the schooling I received at La Notizia, when Enzo Coccia said, “Pizza is not the same as bread,” he wrote down pizza dough’s ingredients in the following order, to demonstrate how the dough is made: (1) acqua (water); (2) sale (salt) plus impasto (stir to dissolve); (3) lievito (fresh yeast) plus impasto (stir to dissolve); and, finally, (4) farine (flour). In Naples they base their ingredient quantities on one liter of water, whereas in French baking we base ingredients on 1 kilogram (2.2 pounds) of flour. This turned on its head my French baker’s method (and my mind-set) of mixing flour and water, letting it rest for 15 to 20 minutes (what we call the autolyse period), then adding salt and yeast, then mixing the final dough. I later confirmed with Mauro Caputo at the Caputo flour company that the water-salt-yeast-flour approach is the typical Neapolitan way to mix pizza dough.

The second big shift in my thinking was to come from everyone in Naples: rather than mixing the dough and letting it rest for several hours to rise (what we call bulk fermentation), it is customary to mix the dough and then divide and shape it into dough balls early on in the fermentation timeline, often just 2 hours later. Enzo makes up his dough balls just 10 to 20 minutes after mixing. This was crazy to me. A bread baker thinks the bulk fermentation period is critical to allowing complex flavors from fermentation to develop, so it’s important to give your dough enough time for that to happen. And a bread baker is also driven to make a loaf that has its maximum possible expansion without collapsing. A pizzaiolo only thinks of managing the dough’s ability to expand in the context of the rim, the cornicione, of a pizza, and knows that a long fermentation at the second stage, in the dough ball, is sufficient to give that complexity of flavors from the dough’s fermentation (the superb, mellow flavor of Enzo’s crust is a testament to his methods and the flour he chooses). Most of the fermentation takes place in the dough balls, called panetti in Naples, which rest for 10 hours before Enzo’s pizzeria, La Notizia, opens at 7:30 p.m. This change in pizza dough management and its timelines was really intriguing to me. I soon learned from other Neapolitan pizzaiolos and the folks at Caputo that a 2-hour first fermentation is the norm in Naples, with no refrigeration and the dough balls all being made into pizza the same night. Enzo takes the timeline to the extreme.

One of Enzo’s kitchen staff brought out a tray of panetti for us to look at just 30 minutes before the restaurant was to open. They were gorgeous: perfectly rounded, with no hint of collapse; inflated and strong from the rise, beautifully smooth, and boasting a lovely, slightly lactic aroma. The resulting pizzas that we enjoyed not long after were delicate, light, savory, and delicious, with just the right slightly crisp exterior and soft crumb on the rim, the bottoms thin and spotted underneath. There was a very nice aftertaste that only comes from good flour and excellent fermentation. I had read about La Notizia’s dessert calzone, and had to try it. We finished with a chocolate lava calzone that took pizza dessert to new heights. When we said our goodbyes and left the pizzeria, there was a lively, stylish crowd on the sidewalk waiting their turn to eat.

Rome

Pizza occupies an important place in Roman life, too, even if it doesn’t have the deep cultural identity and history that it has in Naples. There are flatbreads in Roman history going back to the day of Caesar. One, called pinza, is a plain baked flatbread that is topped with fresh ingredients and olive oil after baking. Today there are two kinds of Roman pizza: bakery pizza, called al taglio (by the slice); and tonda, or round pizzas, also generically called pizza romana, served for dinner at pizzerias that are open only in the evenings. The beauty of Roman pizza in either form is its lightness; it can be a lunch, a snack, or dinner.

Al taglio pizza is a cheap and easy Roman street food. In the States we might call these sheet pizzas. The most common version is quite long—about 4 or 5 feet—and about 10 to 12 inches wide. It’s baked directly on the hearth or in a large rectangular pan inside of a bread oven, then cut into pieces in a size negotiated at the counter. Typically, as at Antico Forno Urbani, the person behind the counter will position a knife at a spot on the rectangular pizza and look to you to say yes, or smaller or bigger. When you give the nod, he or she cuts the pizza, weighs it, folds it in half, and wraps it up with a ticket that you take to the cash register to pay by the gram. Eat it on the go.

Al taglio always has a thin crust—about ⅛ of an inch thick—if it is a basic pizza rossa or bianca; sometimes it’s thicker if the toppings demand a stronger base. This is not a heavy pizza. Very often the al taglio is made without cheese. The toppings are light and flavorful, and the portion sizes are up to you (but not large). Often the pizza is heated and, usually, served folded in half (it’s a pizza sandwich!) and wrapped in paper with a logo. During the lunch rush, around 1:00 p.m. in Rome, the bakery is pulling fresh pizzas out of the oven and thus they don’t need to be delayed with reheating. They are best at this point, with the most moisture and most tender crust.

The basic al taglio pizza is either a rossa—tomato sauce, oregano, and olive oil (my favorite)—or a bianca, baked with a very thin film of olive oil and a light sprinkling of sea salt. “It’s just bread” is what the guy at Pizzarium’s counter said to me when I ordered the bianca. The bianca is baked in rectangular sheets and it’s like a thin focaccia, the same as the rossa but without the tomato. Good al taglio pizza has an airiness to its crumb and the character of a long-fermented dough, texturally and flavor-wise, with that retrogusto, the mellow, fermented, wheaty aftertaste you get when you exhale. The top features a bubbly crust from a gassy dough. The pizza is shaped by hand into long, thin stretches of supple, soft dough and stretched on a floured board that is a little bit wider than the pizza, and about 4 to 5 feet in length. It’s just a thin, light board. The dough is stretched from both sides to elongate, and allowed to rest for a bit. Then it’s stretched lengthwise again, lightly oiled with a wide paintbrush, and pressed (docked) with fingertips, like focaccia. At Roscioli they let it rest and then repeat, stretching it out a third time to get the full length and proper thickness of dough. The board can be used as a peel to load the dough into the oven. Later, the baker will use thin wooden peels about 3 feet in length to remove the pizza when it’s finished. It’s fun to watch these come out of the oven, with the baker’s arms stretched sideways holding 5 feet of pizza as it is transferred to a cooling rack. Things really start to get interesting when the bakery goes beyond the rossa and the bianca to more creative toppings. Shredded potato is very common, as are zucchini and eggplant. Cured meats like prosciutto work well as a topping. Then, more recently, some have been going for more expensive toppings like the terrific pesto-and-burrata pizza I had at Roscioli in the Centro Storico, near the Campo de’ Fiori. Gabriele Bonci has found his own personal stratosphere at Pizzarium, with al taglio pizzas done his unique way: naturally leavened dough made up with whole grain flour and using toppings that push the imagination, from mortadella with a chickpea puree to eggplant with red peppers and arugula to wild mushrooms and garlic on top of shredded potatoes. It’s nice to see a baker go beyond the rules to make a very traditional food his own unique offering.

Al taglio pizzas are baked in bread ovens at temperatures between 520° to 590°F (270° to 310°C). This is several hundred degrees cooler than the wood-fired ovens of Naples. Some are baked directly on the hearth of a deck oven, the same kind also used to bake bread, and others are baked in the same oven but in special baking pans instead of on the hearth. Thicker doughs, like focaccia from Genoa, do well baked in pans that are lined with oil beneath the dough. Thin-dough al taglio pizzas, like the rossa and the bianca, bake beautifully directly on the hearth (only the panned pizzas need oil—or very well seasoned pans—to keep them from sticking).

Rome is also known for its pizzerias open for dinner only, baking super-thin-crusted pizzas in wood-fired ovens. To me, Roman al taglio pizza makers are bakers. Roman pizza makers doing the thin, round pizzas are pizzaiolos. I think they’d agree. The pizza romana differs from Neapolitan pizza primarily in the crust. It is a very thin crust with little to no poof in the rims. When I make these—and I love them—I use half the amount of dough I would use to make the same-size Neapolitan pizza, and I use a rolling pin to make the dough as thin as possible. These pizzas are still baked with a little bit of char on the edges, and a nice black spottiness on the bottoms is the best, coming from a very hot wood-fired oven. Excellent examples can be found at Da Remo in the Testaccio neighborhood, La Rioni near the Colosseum, and Pizzeria Emma in the Centro Storico. And while Rome may not be saturated with great pizzerias the way Naples is, it is the style of this super-thin crust that intrigues me and that led me to create a set of recipes in this book modeled after my ideal Roman pies. The thin, crisp crust is satisfyingly light. I can eat an entire pizza of this style without a heavy feeling in my belly for a somewhat light dinner, or have a fried starter beforehand (common in Rome and Naples), like the fried rice balls called suppli, artichokes, or fried zucchini flowers.

I so love these beautiful pizzas for their crisp, practically crackery outer rim. If they’re topped with sauce and cheese, the moisture will put some sag in the middle. If the toppings are more minimal, the entire pizza might retain its crispness all the way through, depending on the pizzeria and how it’s baked. One of my favorite Roman tondo pizzas has no cheese: it’s topped with tomato sauce and a little oregano, and after it comes out of the oven, cured anchovies and a drizzle of good aromatic olive oil.

THE UNITED STATES

What is American pizza? What did we do to it after it hit our shores?

In the beginning…

New York

In the late nineteenth century, pizza existed only in Naples and the surrounding region, Campania, in southern Italy. It was food for the working class. Between 1880 and 1920, over four million Italians escaped poverty and famine in southern Italy and came to America, a land of hopes and dreams, of plenty and opportunity. Their flight was literally a survival mission. Our nations are forever linked by this event. Our American pizza tradition began with Italian immigrants in New York who brought their gastronomic culture—and their love of pizza, a defining component of their diet—with them.

Lombardi’s became America’s first full-fledged pizzeria in 1905, when Gennaro Lombardi abandoned the grocery business at his store on Mulberry Street in New York City’s Little Italy to meet the demand for his popular pizza. Pizza historian Scott Wiener pointed out to me that pizza was actually sold in bakeries all over Little Italy in 1900. Lombardi’s was the first to sell only pizza, and most likely the first with the word pizzeria on the window. The early pizzas from bakeries in Little Italy were baked in coal-fired bread ovens and the pizzas served to cool down the hearth of the hot preheated ovens, preparing them for bread baking. The first pizzas were different from today, according to Scott’s research: the toppings were Romano cheese, lard, tomato, and oregano, resembling the pizzas of Naples. Mozzarella came later. As in Naples, the emphasis was on cheap, affordable ingredients. The pizzas were, according to Scott, breadlike and soft.

Lombardi’s popularity spawned more pizzerias, established by former employees: Totonno’s Pizzeria Napolitana on Coney Island (1924), John’s Pizza of Bleecker Street (1929), and Patsy’s Pizzeria in Harlem (1933). These places marked the birth of the family-style pizza restaurant in America, at a time when it was still a street food in Naples. Italian immigrants longed for the staple food of their homeland, and for their own businesses, and New Yorkers outside of the immigrant community slowly learned that this ethnic food, a thing new to them called “pizza,” was really good to eat. These immigrants told the world who they were through their pizza. But it was going to take some time. These early-twentieth-century New York pizzerias were mostly serving their own Italian communities. Pizza didn’t really catch on in a big way in New York until after World War II.

Trenton Tomato Pies

Maybe there was a time when the word pizza might have sounded too exotic to draw a crowd. Across the Hudson River from New York City, Trenton, New Jersey, is its own pizza vortex, where they call it tomato pie. First there was Joe’s Tomato Pies, opened in 1910. Then Joe Papa opened Papa’s Tomato Pies in 1912. De Lorenzo’s Tomato Pies opened in 1936. All were run by the families of immigrants from Naples. What’s different about tomato pie? The sauce goes on top of the cheese and toppings. The crust is very thin.

New Haven

Not far from New York City, New Haven, Connecticut, is another place where, in the early 1900s, coal- and coke-fired (hot!) bread ovens were used to bake pizza (coke is converted coal and burns very hot, and is cleaner than coal). But the stories of these historic places go well beyond the pizza itself. It always comes back to the pizza maker. I like this story of Frank Pepe of Frank Pepe Pizzeria Napoletana in New Haven, Connecticut (1925), that romanticizes his heritage and underprivileged beginnings (from their website): “Born in the town of Maiori, on the Amalfi coast southwest of Naples, Frank Pepe was the quintessential Italian immigrant. Poor and illiterate, he immigrated to the United States in 1909 at age sixteen with little more than his health and a strong work ethic. In 1925, with his wife, Filomena, they started making a simple and humble product from their homeland, pizza—or as they would say in their dialect, ‘apizza’ (ah-beets). They baked their pizzas offering two types, tomatoes with grated cheese, garlic, oregano, and olive oil, and the other with anchovy.”

Frank Pepe’s, now run by his five grandchildren, is still iconic today. The neon sign above Pepe’s kitchen reads “The Original Tomato Pies,” and every pizza on the menu is called a “tomato pie.” This makes sense when you think like they do at Pepe’s: that cheese is an optional topping. If you want muzz (see sidebar), you need to ask for it. The Original Tomato Pie has tomato, garlic, oregano, and olive oil and is—as it ever was—topped with grated cheese (grated cheeses as toppings are almost always either Romano or Grana Padano) or anchovy.

Frank Pepe’s was the first of three famous, and now historic, pizzerias in New Haven. Pepe’s was followed by Modern Apizza in 1934 (moved to its present location just two years later, in 1936, when it was called Tony’s Apizza), and Sally’s Apizza in 1938. The style of these New Haven pizzerias, while similar, is not exactly the same. Today Pepe’s and Sally’s still have their super-hot coal-fired brick bread ovens, with the firebox underneath the hearth, while Modern Apizza converted their coke- or coal-fueled brick bread oven to oil-fueled in 1967. Until pizza became more widespread in the United States, there were no ovens that were designed for pizza, because pizza wasn’t a thing yet. All these early pizzerias were making pizza in ovens designed for bread.

Mozz or muzz on the pie? The affectionate slang moniker was adopted from the Neapolitan dialect that remains in use today in corners of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. If you listen to Rosemary Clooney singing “Mambo Italiano,” you’ll hear, “Hey Mambo, no more-a muzzarella. All you Calabrese do the mambo like-a crazy.” Thanks, Rosemary.

Each of these three historic New Haven pizzerias makes pizza from a very thin crust, not poofy on the rims, and charred on its edges. Clam pizza, which was born at Frank Pepe’s, has been widely adopted by other pizzerias, for good reason. Fresh-shucked clams, garlic, olive oil, herbs, and bacon make a beautiful combo. Bobby and Rick Consiglio, two sons of Sally’s Apizza founder Salvatore Consiglio (himself a nephew of Frank Pepe, whose restaurant is where he got his start in the pizza business), continue to make the pizzas at Sally’s to this day.

American Pizza: Doing It Our Way

Family-owned pizzerias, run by moms and pops usually of Italian-American heritage, slowly spread around the country, but without the informational interconnectedness we have today, distinct regional styles evolved. GIs returning to the States after World War II who wanted more tastes of the pizza they had in Italy? Many say they were the catalyst for pizza’s spread beyond Italian-American communities. I asked my dad, born in 1929 and raised in a suburb of Washington, D.C., when he ate his first pizza, and he said it was in the early 1950s and it was called tomato pie. The ubiquity of pizzerias that we see today did not begin for another two to three decades.

The distinct American regional styles fascinate me—like Detroit pan pizza (for example, Buddy’s), the New Jersey thin-crust tomato pie (like De Lorenzo’s), Philadelphia tomato pie (no cheese), New Haven tomato pie, and bar pizzas from the Midwest and East Coast. Then there are the unique pies of Old Forge, Pennsylvania, population 8,300, with about twenty pizzerias all making “trays” of Old Forge pizza in the same style—pan pizza made crisp underneath because of a layer of fat or oil under the dough, with onions in the sauce, and no rules about the cheese, though if you go there they will tell you what’s different about each one. In the next chapter, I’ll go into greater detail about the different pizza styles—but their origin stories are fascinating.

A lot of us grew up eating pan pizza. It’s a very different thing than hearth pizza (for example, New York, New Haven, Roman, and Neapolitan-style pizzas, where the pizzas bake directly on the floor of the oven). There’s a reason pan pizzas are often called grandma pies: it’s a commercial version of the pan pizza Nonna would bake at home. Pan pizzas need some fat to keep the crust from sticking, for one thing. The pan gets a thin film of olive oil, lard, shortening, or some other fat so the pizza can come off it after it’s baked. Some will even remove the pizza from the pan near the end of the bake and finish it directly on the oven’s hearth. But if too much oil or fat is on the pan, then the pizza will leach excess oil or fat onto the oven floor if that’s where it goes to finish the bake, and that’s not good. The oil or fat will smoke and somebody’s gonna be mad. When it’s properly baked, the fat gives the crust a nice little bit of crisp and a flavorful browning, too. In Maryland, where I grew up, there were some pizzerias that had slightly flaky crusts, which can only come from fat or shortening in the dough.

The cheese and the ovens are big differentiators for what makes American, or New York–style, pizza distinct. The low-moisture, full-fat mozzarella cheese used on a good American pizza retains its soft, gooey, stretchy texture and its heat for a long time. You can take it home in a box and it’s good to eat later, whether or not you warm it up. (Neapolitan, by contrast, has a shorter lifespan.)Typical American pizza ovens, modeled after bread ovens, bake at temperatures between 550° and 650°F (290° and 345°C) depending on the pizzeria. The longer baking time at a lower temperature than the Neapolitan wood-fired ovens produces a crisper pizza crust. (For comparison, most of the breads we make at my bakery bake at temperatures from 440°F/225°C—for baguettes—to 500°F/260°C—for levain breads.)

The ubiquitous pepperoni, unheard of in Italy, is a truly great American creation, perfect for crisping up on top of a pizza. Yet it’s hard to pin down exactly what pepperoni is—some is made with beef, some with pork, often it’s a blend of the two—even though it is always characterized by a reddish pigment and a mild spice. It should also be lightly smoky, fine-grained, and semisoft. I don’t care that pepperoni is not Italian. I think it’s a perfect topping for pizza: its meaty, smoky spiciness—with maybe a little puddle of grease in its cup as it curls from baking—goes so perfectly with a good crust, sauce, and cheese.

Pepperoni is a perfect symbol of American pizza evolution: it’s Italian-ish, sure, but more important, it just tastes good on a pie. Today, we have an ever-increasing mash-up of styles and toppings that are all American by virtue of their place and their sense of freedom about what pizza can be. And we continue to innovate and evolve. Some pizzerias, like mine in Oregon, aren’t making pizza to the specific style of other pizzerias so much as we are making pizza that we like, and making it in our own way—although in our case we have a strong Italian influence. Many pizzerias are getting creative with toppings, with some using classic Italian pasta combinations—arrabiata, amatriciana, or cacio e pepe—and others looking to their larder, the season, and their imaginations to see what might go together.

As interesting as the national evolution of pizza in America is, in a way, it all kind of circles back to the original birthplace, New York City. Just like a few of their creative counterparts in Italy, some leading New York pizzaiolos have taken a strong, century-old tradition and really run with it. You want rock ‘n’ roll pizza? Roberta’s in Brooklyn once made a pizza they called Def Aleppo, topped with mozzarella, Parmesan, ricotta, Aleppo pepper, and spring garlic. Or get crazy (and very happy) with Paulie Gee’s (also in Brooklyn) Hellboy, topped with spicy capicola and Mike’s Hot Honey. Oh God, it’s good. Emily, in the Clinton Hill neighborhood of Brooklyn, slings terrific pies with classic, quality ingredients like mozzarella di bufala and Benton’s ham, yet their most popular pie, the Colony, is topped with pickled jalapeño peppers, pepperoni, fresh house-made mozzarella, and a squeeze of honey, post-oven. What’s cool about Emily, Roberta’s, and Paulie Gee’s is they start with Italian methods and boffo Italian wood-fired ovens, then take it their own way with their own inspirations and quality toppings. But the bones are still based on Neapolitan tradition.

Then there are a growing number of Neapolitan pizzerias in Manhattan and Brooklyn—Don Antonio, Kesté, and Motorino—and then, also in Brooklyn, at the aforementioned Paulie Gee’s, Emily, and Roberta’s, plus Franny’s, that are Neapolitan in style but often creatively topped. This Brooklyn family of wood-fired-oven pizzerias is not just an interesting niche; it now represents its own branch on the pizza tree. New York also has thin-crusted bar pizzas, pan pizzas from Adrienne’s, square pies from GG’s, and the particular thin-crust pizza of places like Rubirosa and Joe & Pat’s in Staten Island.

The fact is, even an average crust with sauce and melted cheese still tastes pretty good. For that reason, there are a lot of average pizzas that plenty of people happily eat—and plenty of people for whom pizza is more of a business proposition than a passion for quality. Please ignore them. Then there are purists who have hand-built wood-fired ovens and are using ingredients from Campania as well as their own region, like we do at Ken’s Artisan Pizza and like Mark Hopper, who gets local mozzarella di bufala the day after it is made and imports tomatoes from southern Italy, does at Vignette Pizzeria in Sebastapol, California.

As Americans, we distinguish ourselves with our variety, abundance, and freedom to experiment. And, countering the Pizza Huts of the world, there is now a well-established movement, a rebirth of independent pizzerias committed to artisanal skill and ingredients—not just pizza that sells, but pizza that aspires to greatness. Independent mom-and-pops that have been making quality pies the same way for decades have an important place in American pizza culture. Anything but soulless chain pizza for me, please.

Let’s talk about pizza styles and then cut to the chase and make some pizza.

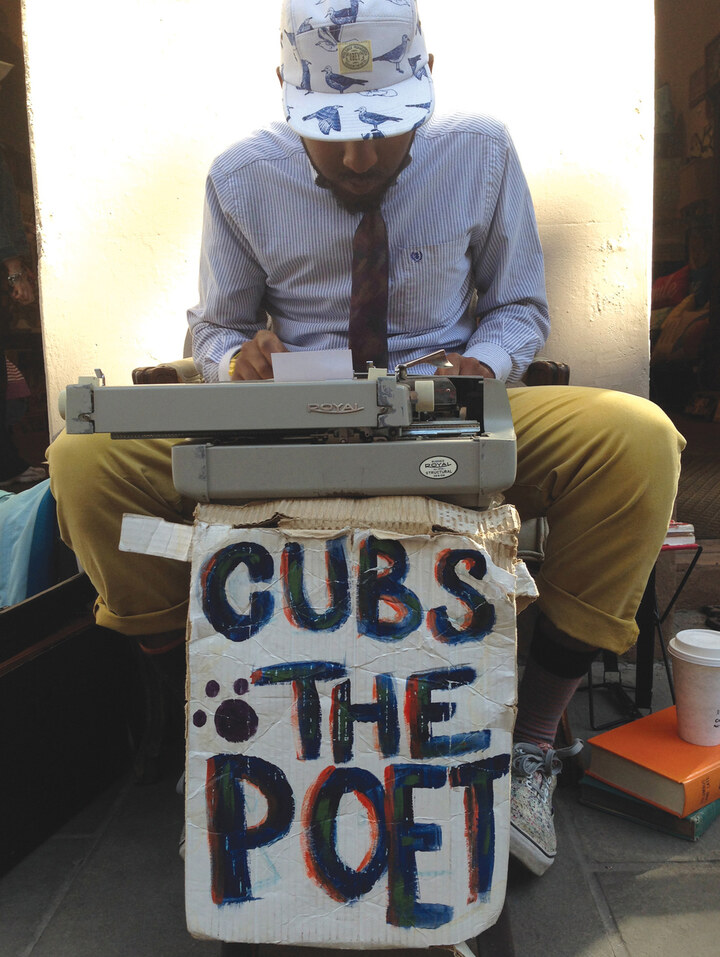

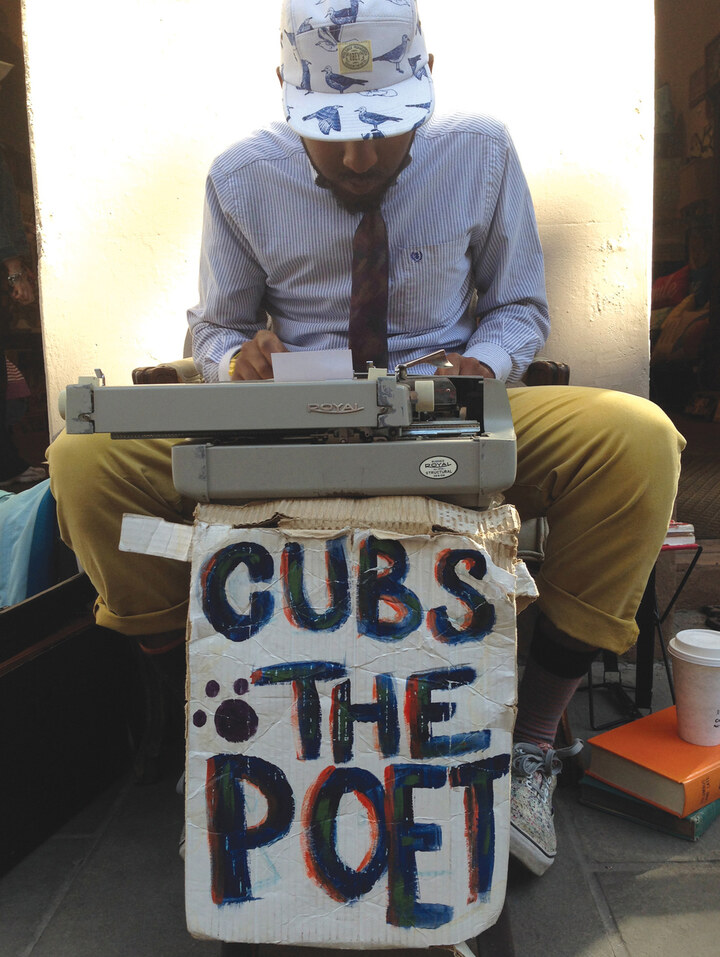

A Slice of Poetry.

By: Cubs The Poet.

Slices sold to society,

crust crushing the

dough . .

Profit passed for passion,

pepperonies, and

cheese, melting the mind.

Stuffed with shines and

cycles of circles,

we toss the taste of

time towards

the dominos of

r

e

a

m

s.

Pizzas & Poetry, purposing

perfect portions

of pieces

fit to fill the

mouth of the masses.

CHAPTER 2

PIZZA STYLES

Do you want to eat the same kind of pizza all the time? Maybe. You could make the same thing again and again, and hopefully get very good at it. But perhaps you’ll wake up one morning craving something new. Or you traveled and had a different kind of pizza that you liked and decided you want to try your own home version of it. The pizza styles represented in this book will give you enough range that you can successfully make a variety of pies and can switch up your repertoire depending on your mood and who you are serving. These styles are a representation of what many great pizzerias are producing in Italy and in the United States.

Many independent pizzerias are making their own style of pizza and don’t want to be pigeonholed into somebody else’s style or concept. In America, we are maybe not quite as rules-bound as other countries. I still have a hard time saying exactly what style pizza we make at Ken’s Artisan Pizza here in Portland: call it wood-fired-oven pizza inspired by Italian pizzas that our chef, Alan Maniscalco, and I have enjoyed. Ours bake in 2½ minutes, compared with Naples’s 60 to 90 seconds, so I can’t call it Neapolitan, but our influences draw more from Italy than, say, New York. Many American pizza styles have their own defining characteristics—a form that is further adapted by each individual pizzeria into something it calls its own. Sometimes the style is something you know when you see (or eat it), but codifying it—putting it into words—is challenging.

The classic New York pizza is thin-crust, mostly crisp, not poofy on the rims, baked on the hearth of a deck oven, and topped with tomato sauce and with cheese that holds its soft texture for a long time after it’s out of the oven. Look around at any Best-of New York list and you will find a glorious combination ranging from coal-oven thin-crust pizzas from places like Totonno’s and the original Patsy’s to slices at joints like NY Pizza Suprema to square pie slices at Prince Street Pizza. And the conversation always comes around to the legendary Di Fara, which stands in a unique place of its own.

There is only one place in the world where the language of pizza has been codified—and even written into law. The Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana (AVPN) and the Italian government went to great lengths to protect their cultural treasure, the Neapolitan pizza. They registered with the European Union and, in 2009, gained approval to classify the specific things that are required to make Neapolitan pizza truly pizza Napolitana, even if it’s made in Phoenix, Arizona. You can be TSG (Traditional Specialties Guaranteed, or Specialita’ Tradizionale Garantita; an Italian-speaking American might say either TSG or STG—it’s the same thing) certified anywhere in the world so long as you follow a set of strict rules, have the right kind of wood-burning oven, and use the right ingredients. Neapolitan pizza is the only pizza with specific definitions and instructions dictating its creation: a dough with just flour, water, salt, and yeast in defined ratios, mixed in a particular way for 20 minutes without raising the temperature of the dough, and then fermented for 2 hours, divided by hand into dough balls (panetti), and fermented for another 4 to 6 hours, with the dough balls to be used any time during the next 6 hours, and baked in an oven averaging 905°F (485°C). There’s much more, but this gives you an idea. These rules and actual certification ensure that a TSG-certified pizza is consistently a very specific pizza, and properly representative of the pride of Naples. I’ve been at a restaurant serving pizza labeled “TSG” and discovered they used a gas-fired oven and their pizza takes several minutes to bake. That just isn’t right.

I love that about the AVPN—that the point was to protect a cultural icon in a region where pizza is part of what it means to be Neapolitan.

Other pizza styles don’t involve government-approved certification. However, there are reference points for each pizza style outside of Naples. A New York pizza is often characterized by a stiff, crisp crust and cheesy toppings and by the facts that it’s eaten by the slice, that there’s not too much poof in the rim, and that the sauce and cheese go almost to the edge of the crust, which is baked golden but not often with a char. In contrast, Rome has its own common examples of simple bakery pizzas: pizza bianca and pizza rossa, crisp but with a nice bit of delicate chew, baked only to golden and cut to order in slices about ⅛ inch thick. And then there are the Roman super-thin, crisp-crust, wood-fired-oven pizzas that I love and think fit a platonic pizza ideal.

This book is about being inspired by regional Italian and American pizza styles to make really good versions at home. We’ll never be able to replicate the pizza that comes from a specific pizzeria. That said, the more you know about the history, style, and tradition of a pizza, and the deeper your affection and respect for that tradition, the better your home version of it will be.

This book is not a comprehensive guide to every style of pizza under the sun. But there are a lot of different types of pizzas in these pages; this chapter introduces the styles and their key characteristics.

NEAPOLITAN PIZZA

In Naples, pizzas are baked in 60 to 90 seconds in wood-fired ovens at around 905°F (485°C) directly on the hearth. At the table they are eaten with a knife and fork. The sauce is nothing more than canned tomatoes—whole peeled tomatoes from southern Italy—pureed with salt. Toppings are simpler and less cheesy than a New York pizza, and the cheese is one of two kinds of fresh mozzarella, either fior di latte, from cow’s milk, or mozzarella di bufala, from water buffalo milk, often with the addition of a small amount of grated hard cheese such as pecorino or Grana Padano sprinkled underneath.

The Neapolitan-style pizza recipes in this book are baked on a preheated pizza steel or pizza stone in a standard home kitchen oven at 550°F (290°C), and finished with the broiler, taking a total of about 7 minutes. Because the home oven is so different from a 905°F (485°C) wood-fired oven, the pizzas you make using this book are going to be different from a real pizza Napolitana, but they’re still great pizzas inspired by the real deal, so why not? At home you get the same size pizza with a poofy rim; the flavorful crust will be crisper than that in Naples (you get a really nice light, crisp, chewy texture in the crust from the home kitchen oven); and you get the bright and savory flavors of tomato and baked cheese on top of it. My recipe has you adding the cheese 4 minutes into the bake so its finished texture resembles the texture of the cheese on a real Neapolitan pizza.

You cannot exactly replicate the methods of Neapolitan pizzaiolos and expect to get their same results if you are baking in a home oven. That may seem obvious, but it’s significant. The AVPN rules state that the allowed hydration in a true Neapolitan pizza is between 55 and 59 percent of the flour weight. This makes a dough that is perfect for baking in 60 seconds in a 905°F (485°C) oven. It is not perfect for baking in a home oven at 550°F (290°C)! The result would be a very stiff crust, crisp and dry, and nothing at all like a tender Neapolitan pizza that you eat with a knife and fork. The bottom of a Naples pizza needs to set very quickly in the hot oven so it can be turned before the side closest to the fire gets burned. A dough above 70 percent hydration is a disaster when baked at 905°F (485°C)—if you try to slide a peel under the pizza once the back of it is getting charred, it turns to soup in the middle because the base isn’t yet set. But a well made 70-percent-hydration pizza dough works great for making a Neapolitan-style pizza in a home oven at 550°F (290°C). With the 7-minute baking time, this dough retains its softness in the middle, although the cornicione (the outer rim of the crust) in the home oven version will be crisper than that of a true Neapolitan pizza. So I make an adjustment to the dough for home oven baking compared with how it’s made in Naples, adding over 10 percent more water to the dough than in the AVPN formula, though I recommend the same 00 flour they use. It’s not to the AVPN’s code, but I maintain you end up with a pizza that’s as close to the Neapolitan spirit as possible.

The desired results for a Neapolitan-style home kitchen pizza are:

• When fully stretched, the dough is 10 to 12 inches across.

• The underside of the crust has dark brown (and occasionally black) leopard spots.

• The crust at the center of the pizza is soft but fully baked; each slice should flop from rim to tip when held up.

• The rim is poofy with visible air bubbles on the inside and splotches of dark brown or black where the crust has charred.

• The cheese is fully melted but not burned, and not completely liquefied.

• All the elements—crust (underside, interior, and rim), toppings, and cheese—reach their perfect point of baking at the same time. In the home oven, finding the ideal rack position helps make this happen.

PIZZA ROMANA, OR ROMAN DINNER PIZZA

With its ultra-thin, crisp crust, Roman pizza is a study in lightness. Like their Neapolitan cousins, these pizzas also bake quickly in very hot wood-fired ovens. The sauce and toppings are also similar. What differentiates the Roman style, though, is the thinness of the crust. The Roman pizza is the same diameter as the Neapolitan pizza, but uses about half the dough. In Rome, some pizzas are crisp all the way through, while some have cracker-crisp outer edges and a soft interior with a little bit of flop to it. This interior texture is determined by the dough hydration (the less water in the dough, the crisper the whole crust will be), the thinness of the dough, the way it’s baked, the amount of sauce the pizza is topped with, and how much moisture is released from the cheese as it bakes. Crispness will vary from one Roman pizzeria to the next. This pizza in its home kitchen incarnation, baking at 550°F (290°C), is going to be pretty crisp all the way through. One of my favorite versions of this style is called a pomodoro (see my version on this page): crust baked with nothing but tomato sauce and a bit of olive oil, then topped with freshly grated pecorino, caciocavallo (a fantastic stretched curd cheese from Campania), or other cheese right after it comes out of the oven.

If you sit down for dinner at a Roman pizzeria in the evening—and they usually open at 7:30 p.m.—you are likely to be served a pizza that has a very thin, light, crackery crust, with just a little give when you bite into it. These are delightful pizzas and are the exact opposite of a doughier, softer Neapolitan pizza. There are also true Neapolitan-style pizzerias in Rome, and some are excellent, but the pizza tonda style (round, wood-oven pizzas) Rome is known for is this thin, almost crackery crust. Toppings are not heavy, but they should be of excellent quality, and not much different from their neighbors to the south: good tomatoes, olive oil, anchovies, perhaps some dried oregano, fior di latte mozzarella, or for an extra 2 or 3 euros, mozzarella di bufala. In season, fresh and semidried cherry tomatoes are a popular topping.

The desired results for a Roman dinner–style home kitchen pizza are:

• When fully stretched, the dough is 12 inches or more across.

• The sauce is spread pretty close to the edge, say a ¼-inch.

• The crust is medium brown with darker spots, very thin and crisp but bubbled at the rim.

• It’s very light to pick up.

• The underside of the crust is spotted dark brown or even black.

• The interior crust is soft to crisp. Slices might not flop from rim to tip when fully baked, depending on the moisture content of the toppings.

• The cheese is fully melted but not burned, with no oil separation.

• All the elements—crust (underside, interior, and rim), toppings, and cheese—reach their perfect point of baking at the same time. In the home oven, finding the ideal rack position helps make this happen.

ROMAN AL TAGLIO BAKERY PIZZAS

In Rome, al taglio (by the slice) pizzas are rec tangles of very simply topped pizza, usually wrapped in paper, that one takes away to eat as a light lunch or a snack. The bianca and rossa are classics; topped al taglio pizzas get a bit more creative.

These pizzas bake one of two ways in Rome: in rectangular steel or other metal pans; or directly on the hearth in oblong stretches of dough, maybe 12 inches wide by 4 to 6 feet in length. (Fun to watch!) The bakeries use mostly electric deck ovens that can also be used to bake bread, and I’ve observed baking temperatures at a few of these bakeries ranging from 520° to 595°F (270° to 312°C).